Sports, Cheating and Betting: Thinking About the Court of Appeal Decision in R. v. Riesberry

If people vote with their dollars, then gambling (legal and illegal) has won the election by a landslide.

If people vote with their dollars, then gambling (legal and illegal) has won the election by a landslide.

In a dollar democracy that probably means sports betting is the leading candidate for president.

Earlier this year Will Hobson wrote this in the Washington Post:

America’s sports gambling prohibition has created what many consider (these things are difficult to measure) the world’s largest black market for sports betting. While nearly $4 billion is bet on sports legally in Las Vegas yearly, an estimated $80 billion to $380 billion is wagered illegally through a shadow industry of offshore online betting houses, office pools and neighborhood bookmakers. Legal or not, the money continues to flow, and a growing number of power brokers advocate legalization so government can tax those billions and sports leagues can track it for signs of corruption.[1]

The North American regulatory framework for sports gaming is fairly complex. It is definitely not uniform across jurisdictions, particularly when internet-based gambling is considered. An already complicated regulatory environment can attract a layer of criminal law scrutiny in Ontario when prohibited performance enhancing drugs are added to the sports betting context.

In Riesberry[2], the Court of Appeal for Ontario considered a fraud-centred criminal prosecution into which performance-enhancing drugs were injected (literally) into a traditional feature of the sports betting landscape, horse racing.

In granting the Crown’s appeal from Mr. Riesberry’s acquittal, the decision

- gives the horse racing industry and others a window into the anatomy of this kind of sports gaming prosecution,

- provides a current consideration of Criminal Code sections traditionally relevant to improper conduct in the gaming context, and

- suggests implications for other sports or athletic contests which act as a magnetic hub for performance-enhancing drug use among the participants and sports betting by the public.

In Riesberry, a licensed[3] horse trainer was charged with dishonesty crimes, particularly fraud in an amount more than $5000 and for “cheating at play”[4]. The Crown asserted that an hour before a race, the trainer injected a horse at the Windsor Raceway with a performance-enhancing drug combination of epinephrine and clenbuterol. The horse ran the race and finished in sixth. About 40 days later Riesberry was arrested on a date when he allegedly attempted to give a horse a needle again.

As in many of the historical criminal prosecutions in North America involving performance-enhancing drugs, the thrust of the case prosecuted at trial was not about any criminality directly arising from using or possessing the drugs themselves.[5]

Instead, the Crown’s position was that the trainer committed a fraud on the public who cumulatively placed bets in excess of $5000 (hence a charge of fraud over that amount) because he

1. deceitfully violated the horse racing regulatory rules against performance-enhancing drug use and possession and

2. subjected the betting public to a sufficiently likely risk to its economic interests by significantly violating the regulatory system for horse racing, depriving them “of their bets” given that they were

(a) deprived of “information about the race that they were entitled to know” (i.e. that the trainer’s horse was given a performance booster) and they were

(b) “also deprived of an honest race” run according to the rules and regulations, something to which bettors are entitled.[6]

On the cheating a play charge, the Crown essentially argued that horse racing was in fact a “game” which could attract criminal guilt if a person pursued it dishonestly (i.e. cheated when s/he played it). In the prosecution’s view, since games which qualified for this charge were defined[7] to include games of pure skill, games of chance and games which are a mix of skill and chance, and since horse racing was a combination game (skill with elements of chance), Riesberry’s dishonest use of PED’s in standardbred horse racing established his guilt.

At trial, the Court decided

- Riesberry knew about the ban on having syringes with prohibited substances at the track,

- Riesberry injected the horse with the prohibited drug combo,

- the purpose of injection was performance enhancement, and that

- Riesberry acted deceitfully.

Still, the trial court concluded the prosecution failed to prove fraud over $5000 because it did not provide evidence about the amount which the public bet, did not prove that the trainer’s deceit had any sufficient connection to a risk that the public would lose the economic interest in its bets, and that even if the evidence showed the public’s economic interests had been deprived, the trainer’s dishonest conduct was too distant a cause in the chain of events leading to any supposed deprivation.

The Court of Appeal unanimously decided that the trial court committed impactful legal errors in its analysis, overturned the acquittals and ordered a new trial.

The Court of Appeal determined the trial court made meaningful legal errors because it

- failed to consider all the evidence since the trial evidence record showed that the Crown had in fact provided evidence about the amount which the public bet,

- incorrectly analysed whether bettors were deprived or at risk of being deprived of an economic interest, failing to approach bettors similarly to investors,

- improperly relied on a precedent case (R. v. Vézina, 1986 CanLII 93 (SCC), [1986] 1 S.C.R. 2) that was meaningfully dissimilar to the Riesberry circumstances on a key fact and, consequently, incorrectly assessed how distant the horse trainer’s dishonest conduct was in causing any deprivation or deprivation risks to bettors on the race, and

- improperly relied on an American case that found horse racing was a game of pure skill, failing to recognize that the legal framework for the American decision only contemplated two game categories (pure skill versus chance) and did not contemplate combination games of mixed skill and chance, a category available in Canada under the Criminal Code.

Riesberry seems informative and suggestive.

Horse racing (thoroughbred, standardbred, harness) and other gaming participants are given a look at the nature and range of evidence that the Crown can employ in a prosecution premised on the concept that performance-enhanced cheating defrauds the betting or gaming public. In Riesberry, the Crown’s evidence included testimony, surreptitious video recordings, physical evidence/exhibits (for example, a syringe with its contents), scientific testing results/reports (revealing the presence of an epinephrine and clenbuturol combo), and expert veterinary evidence.

In addition, Riesberry reiterates both the core facts which must be proven before an accused person is guilty of the committing the acts which define the crimes of fraud and cheating at play, and the guilty state of mind which the accused must possess when committing those acts. Significantly, Riesberry articulates these core facts which must be proven in the fresh context of the betting or gaming public’s relationship with the direct participants in the contest, event or game who may adopt rule-breaking performance enhancements that can impact the outcome.

Finally, Riesberry may have implications beyond trainers, jockeys, punters and ponies.

The horse racing industry seems in tangible decline.[8] The same, however, cannot be said about professional hockey, basketball, baseball, soccer or football (particularly the N.F.L. brand), or about the avalanche of gaming (especially if fantasy sports games are included[9]) associated with those sports in the U.S. and Canada.[10]

Performance enhancement offences contrary to league rules and regulations in professional team sports are definitely part of the mix. Arguably, cheating in its various flavours is common.

Nothing in Riesberry suggests that Ontarians who bet on professional team sports are any less at risk of being deprived of relevant information or fairly-contested games when team sport athletes, trainers or managers secretly participate in performance-enhancing drug use, bribery schemes, spying or…(gulp…)…unauthorized modification of game equipment.[11]

While the skill of today’s athletes is imposing and impressive, professional team sports have hardly been denuded of the elements of chance. To date, among other things, N.F.L. games still start with a coin flip, leading scorers blow out their knees by happenstance, and pucks hit weird spots on the ice and bounce over goalies into the net.

While the geographical jurisdiction to prosecute in Ontario was obvious in Riesberry because all relevant actions occurred in Ontario (i.e., the racing, the regulation of the racing, the cheating and the betting), proper jurisdiction would be a prerequisite if an interest existed in, for example, prosecuting matters involving Ontarians betting in Ontario on professional sports played outside Canada (for example, N.F.L. games played in Foxborough, Massachusetts), regulated by leagues headquartered and operated outside of Canada.

Even if all the central legal requirements existed to initiate this kind of prosecution, prosecution offices would still have to decide, as a matter of policy and resources, whether pursuing these kinds of cases would be in the public interest.

Very recently, the Supreme Court of Canada unanimously affirmed (7:0) the Court of Appeal’s decision.[12] Accordingly, once Canada’s highest court reveals its analysis (the S.C.C. indicated that its reasons will be provided later), Riesberry is poised to be a precedent across Canada.

_____________________________________________

[2] 2014 ONCA 744; 122 O.R. (3d) 594 (C.A.) [“Riesberry”]: http://canlii.ca/t/gf339

[3] The respondent trainer worked with standardbred horses rather than thoroughbreds and was licensed under the Racing Commission Act, 2000, S.O. 2000, c. 20 which meant he was governed by the Ontario Racing Commission’s Rules of Standardbred Racing: Riesberry at para. 1.

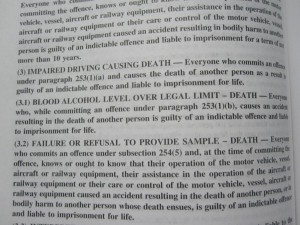

[4] Section 209, Criminal Code of Canada

[5] See for e.g. baseball stars Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens were prosecuted for perjury and obstruction of justice(http://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/mlb/2014/09/17/barry-bonds-appeal-heads-back-to-court/15779621/) and obstruction of Congress, false statements and perjury (http://www.cnn.com/2012/06/18/us/clemens-trial-verdict/), respectively.

[6] Riesberry at paras. 20-22

[7] Section 197, Criminal Code of Canada

[9] http://www.forbes.com/sites/leighsteinberg/2014/08/29/the-fantasy-football-explosion/; http://www.wsj.com/articles/nfl-player-sues-fantasy-sports-company-fanduel-1446262574

[11]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deflategate

[12] R. v. Riesberry, 2015 CanLII 65222 (SCC): http://canlii.ca/t/glltw

Photo Source: http://www.betyourluck.com/sports-bet-tips/nfl-bet-tips.html