The Queen versus Jian Ghomeshi: It‘s Not “That” Case

If you searched court house dockets past and present, no doubt you would find unknown and obscure cases (and maybe some better known ones) where the backstories and courtroom events demonstrate the challenges women can face as the alleged victims and primary witnesses when they allege domestic or sexual assault.

The Queen versus Jian Ghomeshi (No. 1)[1] is not like those cases.

No amount of “I believe survivors” hashtagging, activism on the court house steps, or media availabilities for complainants pre-, post- or during the trial can transform one of the most publicized and most public Canadian criminal cases in ages into the main exhibit for a narrative about injustice to women when they allege violence and indignity by men.

To be clear and obvious, violence against women by men is engrained in Canadian and global history and reality. Criminal justice, like other institutions, has evolved to recognize and arrest key gendered myths in sexual assault law that abused women’s equality rights and distorted the truth-seeking function in criminal trials. That evolution is ongoing.

The decision in and circumstances surrounding the Ghomeshi case, however, do not “roll back the clock” on equality for women complainants.

Ghomeshi’s case does not show that criminal courts are tone deaf on the question of stereotyped analysis of alleged sexual assault victims. It shows that the ears of the court, even in sensitive, notorious cases, are still attuned to the frequency at which collusion, deception and significant inconsistencies are broadcast from the witness box.

It is not a case in point about abusive cross-examination of traumatized women by defence lawyers or the inadequate resourcing of support services. If someone has a transcript of testimony showing repeated Crown objections to any supposed unfair, excessive cross-examination of the witnesses, who had a wind of lawyers, counsellors, advocacy groups, academics, media members and sitting politicians at their backs, then please, by all means, share it with us.

It is definitely not the proof some seek to buttress arguments about switching the burden of proof and placing it on male accused, forcing accused men to testify and diluting the presumption of innocence in sexual assault and perhaps other “gendered” criminal cases.

If the circumstances and facts of The Queen versus Jian Ghomeshi do not support the talking points insistently grafted onto it by an animated public discourse, what might we take from this case?

Try these on for size:

- Suggestions that the unreliable evidence given by the complainants in the Ghomeshi case is a product of the inherent lack of legal resources for sex assault complainants preparing to testify are groundless. The women at the centre of the Ghomeshi evidence, in stark contrast to most domestic and sexual assault complainants, had lawyers to individually represent them. Assuming their lawyers fulfilled their most basic duties to educate their clients, the idea that these witnesses were ignorant of the system and that ignorance led them into inconsistencies or deception makes no sense. In fact, if preparedness to testify is a function of the amount of legal support available, then these witnesses should have been among the most prepared assault complainants going;

- Some commentators who have appeared in Canadian media to opine on R. v. Ghomeshi have, arguably, critiqued the justice system in ways that may leave the impression that they do not truly support foundational principles of fundamental justice and core propositions about advocacy found in rules of professional responsibility. While non-lawyer activists and commentators are free to take a blow torch, chainsaw or Fliegerfaust rocket launcher to the justice system, licenced lawyers are not. Although lawyers are directed to try to improve the justice system with legitimate, considered proposals, they are obligated to “encourage public respect” for “the administration of justice” and warned against, among other things, “weakening public confidence in legal institutions or authorities by irresponsible allegations.”[2] Some may want to turn their mind these directives before launching their next comments on the Ghomeshi trial judge or the Crown lawyers who handled the case;

- If the criminal justice system transformed “I believe survivors” into a legal principle and a presumption every time a woman took the stand in a domestic or sexual assault case with a male accused, it would create the risk of discrimination against other equality-seeking groups, including some who, arguably, have faced and continue to face systemic discrimination in the criminal justice system. Think of this uncomfortable scenario: a white female sexual assault complainant who is the model of Western beauty standards and, in this scenario, the manifestation of white privilege, and an unmistakably black male accused who doesn’t always speak the “Queen’s English” and is reflexively defensive from years of deprivation and/or real and perceived racism. She is presumed to be telling the truth under a theoretical “I believe survivors” reversal of the presumption of innocence. The black man, the focus of disproportionate police attention and suspicion, and tainted with historical stereotypes about his sexual aggression and desire for white women has to prove that he didn’t do it. What could possibly go wrong?[3]; and

- In successfully defending an unpopular client with a robust defence that relied on deeply grounded, non-speculative cross-examination (why speculate when you have a gazillion e-mail messages and photos to rely on), defence counsel Marie Henein provided more evidence of why she’s a leader in the defence bar and the legal profession generally. But, because she’s a woman, self-anointed arbiters of gender loyalty have attacked her for taking the case and, I guess, doing such a good job[4]. Undoubtedly, lawyers of any gender are privileged in some sense and defence lawyers to Canada’s elite like Ms. Henein are very well compensated. But the record is clear: women in criminal law (and in law generally) face a slate of challenges due to gender. Why should a woman at the top of her game and profession have to deal with yet another challenge for doing her job and crystallizing her professional obligation to her client – “to raise fearlessly every issue, advance every argument and ask every question, however distasteful, that the lawyer thinks will help the client’s case and endeavour to obtain for the client every benefit of every remedy and defence authorized by law. “[5]

________________________________________________________________________

[1] Note that Mr. Ghomeshi has a second trial upcoming on or about June 6, 2016

[2] A requirement under the Law Society of Upper Canada (Ontario), Rules of Professional Conduct: Chapter 5 – Relationship to the Administration of Justice, Section 5.6 – The Lawyer and the Administration of Justice, Rule 5.6-1 (Encouraging Respect for the Administration of Justice), Commentaries 1 to 4

[3] There is no suggestion in R. v. Ghomeshi (No.1) that the nationality or ethnicity of the accused was in issue for any reason at any time in the proceedings. However, as a sidebar, it is noted that Mr. Ghomeshi is a U.K. born man of identifiably Persian descent and all the complainants are white.

[4]One wonders what those who accuse Ms. Henein of gender treason would think of the Honourable Madam Justice Michelle Fuerst, a leading Superior Court of Justice trial judge (the one who recently sentenced Marco Muzzo to 10 years imprisonment in the tragic impaired driving causing death case involving the Neville-Lake family), herself a former distinguished criminal defence lawyer prior to her appointment to the bench who is the author of Defending Sexual Assault Cases, 2d ed. (Toronto: Carswell, 2000). Is she wrong to convey her knowledge and guidance on the subject to defence lawyers who may use it in a robust defence against accusations from female complainants?

[5] A requirement under the Law Society of Upper Canada (Ontario), Rules of Professional Conduct: Chapter 5 – Relationship to the Administration of Justice, Section 5.1 – The Lawyer As Advocate, Rule 5.1-1 (Advocacy), Commentary 1 – Role in Adversarial Proceedings

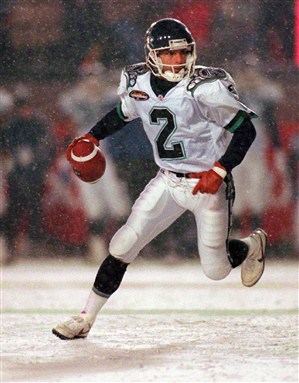

Image Source: http://i.cbc.ca/1.3433634.1454604706!/fileImage/httpImage/image.jpg_gen/derivatives/16x9_620/ghomeshi-trial-20160204.jpg